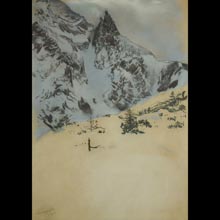

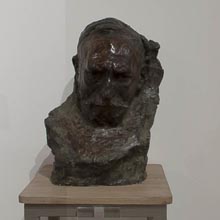

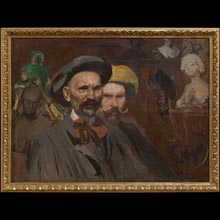

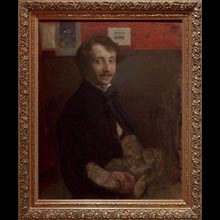

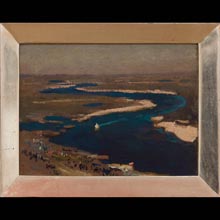

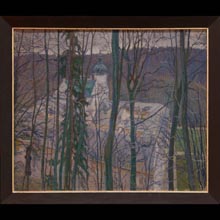

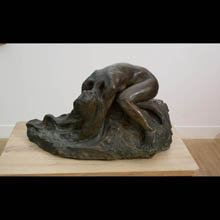

The Young Poland section of the Gallery of 20th-Century Polish Art starts with an artistic introduction to the climate of the period. That atmosphere was largely fuelled by an end-of-century vogue for philosophical works by Friedrich Nietsche and Arthur Schopenhauer, in Poland paralleled by the decadent views of Zenon ‘Miriam’ Przesmycki, Karol Irzykowski, and, above all, Stanisław Przybyszewski. The installation opens with the sophisticated symbolism of Witold Wojtkiewicz (1879–1909) in the vein of the decadent fin de siècle, which André Gide described as ‘...a disturbing and very personal fusion of Naturalism, Impressionism and grotesque.’ Born out of intellectual analysis of personal and collective anxieties and phobias, this world is evocative of somnambular and dream visions interlaced with images from children’s stories. It is populated by lame dolls, puppets, obnoxious manikins and palubas, or “ugly and disgusting biddies”, described in Karol Irzykowski’s “psycho-moral treatise” under the same title. They are put in a degraded, sickly landscape to take part in strange, dramatic and grotesque ceremonies and games, as in Fantasia (1906) or Meditations (1908). Decadent moods akin to Stanisław Przybyszewski’s views prevail also in the work of Wojciech Weiss (1875–1950), for example Totenmesse (1898), a portrait that transgresses the conventional limits of its format; the symbolic Self-Portrait With Masks (1900) with ironic and metaphorical undercurrents; or the 1904 piece Demon (In a Café), created no doubt upon reading Przybyszewski’s De profundis, where a specific decadent aura went perfectly together with the atmosphere of fin de siècle. Human misery and drama fomented by an intense experience of life and death became a subject for sculptors. One example is A Woman in Despair by Konstanty Laszczka (1865-1956), a motif the artist reworked several times. One of the key subjects in the art and literature of Young Poland were attempts to define the sources and sense of artistic work as well as the identity and condition of the artist himself: an outstanding personality , a chosen one and a genius obsessed with art, hence enjoying the privilege of unbridled individualism and subjectivism. However, this superiority went together with a feeling of loneliness, alienation and lack of understanding by people around. A legacy of Romanticism, these subjects were raised in many debates and literary or artistic manifestos in the age of Young Poland. Stanisław Przybyszewski was the key protagonist of the theory of supremacy of great art, and a champion of absolute freedom for the brightest individuals, including the right to establish their own ethical codes. These issues were underscored in visual arts by emphasizing artists’ personal subjectivity, examples including Self-Portrait with Laszczka by Leon Wyczółkowski (1852–1936); a portrait of the smiling Leon Wyczółkowski by Konstanty Laszczka (186–1956); Self-Portrait with the Vistula in the Background and Portrait of Stanisław Witkiewicz by Jacek Malczewski (1854–1929); Self-Portrait with Masks by Wojciech Weiss; or Portrait of Henryk Szczygliński by Ksawery Dunikowski (1875–1964). The spirit of Romanticism surfaced in Mickiewicz’s Imprivisation (1898–1902) by Wacław Szymanowski (1859–1930): by capturing the poet at the moment of fainting after an inspirational recital, Szymanowski voiced his belief that a creative act is a moment of communication with the Absolute; it is a divine frenzy during which a poet turns into a revelator of a greatest mystery. The subject of existence in a cosmic and human dimension spreads through works by Władysław Podkowiński, Gustaw Gwozdecki and Bolesław Biegas, confirming both the religious syncretism of Young Poland and the influence of Arthur Schopenhauer’s ‘philosophy of death”. Chopin’s Funeral March by Władysław Podkowiński (1866–1895) is the artist’s last, unfinished, piece, inspired by Kornel Ujejski’s poem A Funeral March from the series Explaining Chopin. This dramatic, visionary night scene of the funeral of his sweetheart, laden with the symbolism of passing, was, in fact, a cry of the dying artist. The Apocalypse by Gustaw Gwozdecki (1880–1935) contains a catastrophic and totally pessimistic message unveiling the limitlessly tragic abyss of the painter’s thoughts. Universe by Bolesław Biegas (1877–1954) provides an example of transposition of the theosophic concepts of cosmogony and perfect harmony of the universe. The symbolic oeuvre of Jacek Malczewski (1954–1929), was a distinct art phenomenon: imbued with the spirit of Romanticism, interpreting the world orphically, manifesting the power of creative imagination, and emphasising the personal, spiritual dimension of art. In it, reality coexists on a par with imaginary visions, fantastic creatures, angels, biblical and literary characters that accompany his friends he portrayed. The painter depicts himself as different personas: a guiding spirit of art, Anhelli or an androgenic genius. The landscape of his home region of Mazovia or villa districts of Krakow provide background for the visionary scenes: with great sensitivity, usually metaphoric, and subordinates to the overall symbolic meaning. Landscape was particularly popular in the painting of Young Poland, not so much to foster objective reflection of reality as to evoke the artist’s mood in the majority of cases. Treated symbolically as a counterpart of the ‘inner landscape’ of the artist’s soul, it often pictured gloomy, mist-covered autumn sceneries with heavy cloud weighing down on them, nostalgic winter views, or nocturnes: evening or night views haunted by a premonition of death or provoking thought. Landscape conveyed the ominous power of the elements and the untamed, eternal nature interpreted pantheistically as a result and trace of God’s permanent present. Józef Pankiewicz (1866–1940) was a master of lyrical mood. Following a period of glittering Impressionism in his career, he produced a series of nocturnes that disclosed his outstanding ability to perceive a wide range of hues and tones in achromatic colours. Droshky in the Rain (1893) with light reflections on the wet pavement, and the intriguingly mysterious Swans in the Saski Garden (1896) are among the artist’s best achievements, with a colour palette narrowed to nuanced shades of white, grey and black. Among painters, Leon Wyczółkowski (1852–1936) was another passionate landscapist. He executed landscapes in various techniques: in painting (oil, watercolours), drawing (pencil, charcoal, pastels) and printmaking (he used nearly all printing techniques, and experimented by modifying and mixing them). This great artist and lover of nature painted limitless sweeps of Ukraine’s lands or Lithuania’s nostalgic flatlands with the same suggestiveness as he achieved in the ecstatic power of the mountains or charming back alleys of Krakow, the latter combining objective observation with subjective impressions. From the end of the 19th century Wyczółkowski eagerly drew of the subject of the Tatras. The best works of that series were the recurring attractive views of the lakes Morskie Oko and Czarny Staw, Mount Nosal, the Chałubiński Gateway, Mount Mnich, the Temnosmrečinska Forest, and the valleys of Kasprowa, Bystra and Kuźnice, which date back to 1904–1905. He strove to capture the mysterious power of these mountains and the unrepeatable poetry of the places. Whether painted in wintertime or summertime, they render the subject in a unique way, preferably on misty or cloudy days, occasionally at twilight, betraying the influences of Japanese art and James McNeill Whistler’s theory of atmospheric painting. The renown of Young Poland landscape painting from Krakow was further bolstered by the oeuvre of Julian Fałat (1853–1929), a master of watercolour landscapes with a predilection for winter subjects. The artist recycled the motif of snow-capped river banks in various media (oil and watercolour), producing Impressionist-like compositions of interesting colour schemes based on contrasts of blues and whites that were broken by bright light reflecting in them. Fałat initiated reforms in Krakow’s School of Fine Arts. In 1897 he invited Jan Stanisławski (1860–1907) to take the post of the head the Landscape Painting Department. Stanisławski’s oeuvre reigns supreme in the history of Polish landscape painting. He refreshed the methodology of teaching landscape painting by taking students outdoors for sessions, teaching them how to look at nature and spot both its everlasting power and recurring, or even sudden changes. He paid much attention to the skill of capturing the essential signs of beauty at a given point in time. He was himself a master of small, enchanting and expressive landscapes painted with wide brushstrokes: initially realistic, then Post-Impressionistic, and finally expressive views of Ukraine, the mountains and the Krakow region. The monumental Poplars Over Water (1900), is certainly the most outstanding of the artist’s works on view in the Gallery. This symbolic, terrifying image of nature that yields humbly to gusting wind, is painted with the panache of broadly laid patches of colours, among which darks greens, emeralds and greyish blues dominate, with occasional highlights of white clouds warmed by the sun and the sapphire sky. The silhouettes of the stooping trees and the clouds are Secession in style to bring out the expressive values of the composition. Jan Stanisławski gathered a group of students around himself, among them Józef (1872–1947) and Stanisław (1878–1954) Czajkowki, Henryk Szczygliński (1881–1944) and Stanisław Kamocki (1875–1944). They all put into effect the message they had often heard from their mentor: “Gentlemen, paint the Polish countryside because it may no longer exist a few years from now”. After Stanisławski’s death Krakow’s Landscape Painting Department was taken over by Ferdynand Ruszczyc (1870–1936), an artist trained in Sankt Petersburg’s Academy and subsequently associated with the Warsaw and Vilnius art communities. His dreamlike Winter Tale (1904) leaves the viewer enraptured by its calm mood and fairy-like decorativeness, whereas the dramatically expressive nocturne A Mill by Night (1898) conjures up symbolic connotations. The Academy in Sankt Petersburg educated not only Ruszczyc, but also the perfect landscapist and portraitist Konrad Krzyżanowski (1872–1922), who was associated with the Warsaw artistic milieu. His Clouds in Finland (1908) and Golden Stone (1908) are emotive and expressive landscapes rendering superbly the specific look of the Scandinavian coast. Billowing clouds over a placid, cold seashore are the main subject of the former; the latter shows sharply creased magnificent rocks pounded by silvery waves of a bay. Urszula Kozakowska-Zaucha Wacława Milewska