Avant-garde

![Street Juggler [probably author’s replica executed before 1960]](_XX/FOTO/m_XX093.jpg)

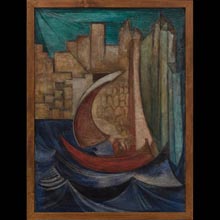

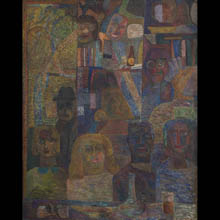

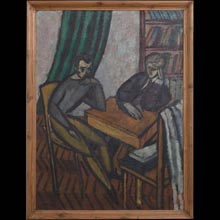

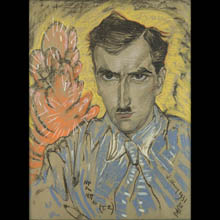

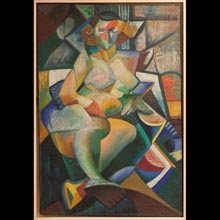

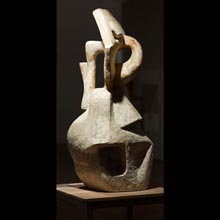

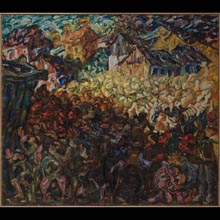

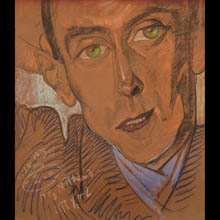

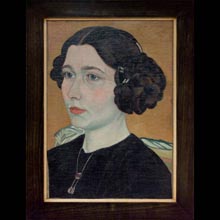

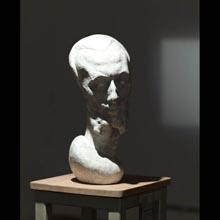

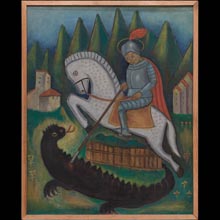

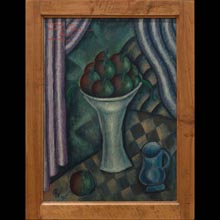

The Polish Expressionists came to existence as an avant-garde art group in Krakow in 1917. Their programme and achievements radiated onto the artistic communities in Warsaw, Poznań and Lviv. For the founders of the movement, later dubbed “the Formists”, it was most critical to come up with innovative methods of rendering form, space, movement and colour. “That aim brought us together two years ago under the slogans of expressionism, which was only used to stand for protest against official art ”, wrote Leon Chwistek in the catalogue for the Third Exhibition of the Formists in 1919. Another, equally important thing was to identify and explore new, vernacular sources of artistic inspiration: folk woodcarving and glass painting from the region of Podhale. The Formist movement, which acknowledged the priority of form over the semantic content of a work of art, fathered Polish modern art. However, the group was not uniform stylistically: what united them were a general idea of creating innovative art and affiliation with European art movements: Cubism, Futurism and Expressionism. Leon Chwistek (1884–1944), a philosopher, mathematician, art theoretician, author of the treatise The Multitude of Realities in Art was one of the leading ideologists of Formism. His Fencing Match (ca. 1919), highly representative for his style and already a classic today, draws on Italian Futurism in terms of form and the way movement is captured; The City (ca. 1919) proclaims typically Italian avant-garde fascination with large cities, and presages the zoned compositions he created after 1925, where an image was based on a harmony of forms, rhythm and colour. Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz aptly described Zbigniew Pronaszko (1885–1958) as “a classic example of a painting sculptor”. His sculptor’s eye is detectable most of all in the construction of the paintings dating from the Formist period, which were built from compact geometric and crystalline shapes that gave the images a cubist and expressive slant, e.g. A Formist Nude (1917), or A Nude in an Interior (ca. 1920). But Pronaszko’s Formism peaked in sculpture, where he coupled patterns from French Cubism with those from Podhale woodcarving. This blend was particularly apparent in the unexecuted design of a Monument to Adam Mickiewicz (1922–1924) for Vilnius, where he introduced angular, geometrising forms. He achieved similar effects in other Formist sculptures such as the perfect Portrait of Tytus Czyżewski (1922) or a design for a Monument to Boleslas the Bold (1922). The Formists included also painters inspired by folk paintings on glass: Tytus Czyżewski (1880–1945), who borrowed their iconographic types and primitive form, and Konrad Winkler (1882–1962), an art critic and theoretician and a painter, who consistently processed primitive forms derived from Podhale’s art of painting on glass after the Cubist fashion. Counted among the Formists are also Leon Dołżycki (1888–1965), who used succinct, synthetic and clear-cut contour lines, and Jan Hrynkowski (1891–1971), who drew on what is termed “Cézanne Cubism”, later a member of the Colourists’ union called “Jednoróg” (Unicorn). During the brief (only a few years long) but nevertheless heroic period of the group’s activity, the Formists were also joined by Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz or Witkacy (1885–1939), who contributed his own, new reflections on art. His philosophical treatise New Forms in Painting and the Resulting Misunderstandings (1919) assumed that Pure Form, totally independent of reality, could be achieved in a work of art. In 1915–1922 Witkacy created a series of full-colour compositions giving them literary titles like A Composition with a Dancer (1920), Mary and Burek on Ceylon (1920–1921) or The Temptation of Saint Anthony (1916–1921), in which he sought to apply the theory of Pure Form. A supreme artistic personality of the two interwar decades, a playwright, philosopher, photographer, painter, and an indefatigable experimenter and provocateur, Witkacy stopped looking for Pure Form in painting in the early 1920s. In 1924 he established a unique art institution, the one-man Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz Portrait Painting Firm, which, like a true artisan’s workshop, drew pastel portraits for pre-set fees and in line with the restrictive Rules he published. It produced income for Witkiewicz, nevertheless the artist hardly showed much respect for his clients (usually except his more or less close friends): Today or tomorrow I need to get your sucker’s face fixed on claret-coloured paper The sessions often turned into farce so that Witkacy could avoid conflict between paid work and his philosophy of art. The artist invented and acted out the characters of the footman Witkaś or the doorman Witkasiński (both variations on his surname), who helped the clients into their coats and hats and, bowing low, saw them to the door. Typically for avant-garde movements both in Western Europe and in Russia, their members and followers combined artistic radicalism with social and political one. The same was true about Poland, where artists held definitely leftist views whether they were tied with Constructivism, which developed mainly in Warsaw Łodz, or with Expressionism in Poznań, or with the multifaceted Krakow avant-garde. In Krakow, students of the Academy of Fine Arts, who were generally pro-Communist, instigated a revolt against anachronistic and “reactionary” trends in art and teaching methods, “persecution of creative imagination”, disciplinary restrictions, as well as the academic establishment’s monopoly on official artistic activity. Among the rebels were Leopold Lewicki, Stanisław Osostowicz, Jonasz Stern, Sasza Blonder, Henryk Wiciński and Maria Jarema. In 1933, they set up the Grupa (later renamed the First Krakow Group) which was to fight for modernity in art and social life. “The pre-war Krakow Group,” Jonasz Stern recalled, “started out with political issues. They were key for some of us, let alone Lewicki or myself. Artistic problems were secondary, which was why they had to match up to the political ones”. That was the reason why some of the members of the Grupa took up socially engaged topics in their paintings and prints. Pre-war paintings by Jonasz Stern (1904–1988) fitted somewhere between Cubism, Surrealism and Colourism. The Nude (1933), cubistically articulated and far from a realistic look, can be viewed as the painter’s artistic credo and a negation of the Academy’s aesthetics promoted by “Young Poland” professors. Sasza Blonder (1909–1949) oscillated between representational painting and abstraction; Adam Marczyński (1908–1985) brought elements of Cubist construction to his still lifes; Stanisław Osostowicz (1906–1939), a painter of small town scenes and the monumental Peasant Epopee (1932), drew on Expressionism; Leopold Lewicki (1906–1973) looked for inspiration in Italian Futurism, French Purism and German Expressionism (Prisoners’ Walk, 1932–1938); Franciszek Jaźwiecki (1900–1946), a talented landscapist and portraitist, achieved effects close to Expressionism by means of various deformations and laying thick textures of densely applied paint; the sculpted oeuvre of Henryk Wiciński (1908–1943) merged monumental elements harking back to Xawery Dunikowski, with Cubism and Neoplasticism; Maria Jarema (1908–1958) made references to the organic world by breaking up the structure of forms. Periodically, the room of the Avant-Garde surveys photomontages by Kazimierz Podsadecki (1904–1970) and Janusz Maria Brzeski (1907–1957), two representatives of Barbarism who organised the most important manifestation of photographic and film-making avant-garde at the First Exhibition of Modernist Photography in Krakow in 1931. The installation is rounded out by a contemporary reconstruction of an experimental film by Jalu Kurek (1904–1983), (from Obliczenia Rytmiczne – Rhythmic Calculations) dating from 1934, which illustrates the artist’s progressive film theories. In this part of the Gallery, a separate place on the mezzanine is reserved for a post-war representative of the Krakow Group, Marek Chlanda (b. 1954), a sculptor, installation artist, draughtsman and performer, who bewildered audiences with uniquely constructed series of artworks (Apocalypsis cum figuris, 1991), or multi-element sets arranged on a floor or climbing upwards (Terminal, 1982–1985). Chlanda’s installations are showed on a temporary basis because the mezzanine is occupied by periodical shows. Urszula Kozakowska-Zaucha Wacława Milewska