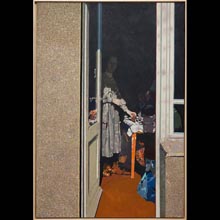

material: tempera, acrylic, linen

dimensions: 200x137

author's label: Signed and dated upper right: Zb.1980; on the reverse the inscription: Zbysław Marek Maciejewski [...] SIMPATHIQUE, [...] 1980

exposition: The Gallery of 20th Century Polish Art,

The Main Building, 1, 3 Maja Av.

key: Colourism <<<

Polish artists’ interest in colour in the 1920s and 1930s was foretold by Józef Pankiewicz’s Post-Impressionist painting. His studio at Krakow’s Academy of Fine Arts soared in popularity among the students. The professor fired their imagination with conversations about early and contemporary art, Parisian museum and galleries, his friendship with Bonnard and curremt trends. In 1923 a group of Pankiewicz’s students set up what they called the Paris Committee – a community of those desiring to go to France to continue their education. They sought to create “good, pure” painting, i.e. painting free of any literary burden or historical and political responsibilities. The aim was to see reality through colour; to express light, space, shapes and other features of forms and events through colour. The motto: peinture – peinture! best summarised that approach. The chief ideologist of Kapism (from the Polish abbreviation “KP” for the Paris Committee) and the author of its artistic manifesto was Jan Cybis (1897–1972), a journalist, painter of dynamic, textured compositions that explore intensive, saturated colours and their mutual tensions. Another figure that dominated in the Krakow community of the Kapists was Zygmunt Waliszewski (1897–1936), a painter deeply rooted in French Post-Impressionism, and a suggestive illustrator of grotesque who used a classic, rich colour palette. Subtle Colourism marked the oeuvre of Hanna Rudzka-Cybisowa (1897–1988), who employed the pointillist technique to put down sensory interpretations of landscape, still life, and portrait. Like her husband Jan Cybis, she used distinct texture which not only accentuated the materiality of pigment, but also had a compositional function of integrating the image. Located between expression and impression, the creative output of Artur Nacht (later known as Nacht-Samborski, 1898–1974) from the very beginning stayed away from the radical Kapist programme. His clear, static compositions and sophisticated combinations of warm and cool colours had their dynamics enhanced by a discrete play of values. The painting of Józef Czapski (1896–1993) developed slightly diverging from the Kapist doctrine: both in the 1930s and, above all, in his post-war work, he opted for expression rather than the postulated colour to illustrate the ordinary, sometimes brutal day-to-day reality. Piotr Potworowski (1898–1962), initially also associated with the Paris Committee, gave up on Kapism and turned towards allusive abstraction using colour to boost dramatic tensions in his highly synthetic landscapes. A lot of Kapists returned to Poland in 1930–1931. As Czapski put it, they felt to be “advocates of absolute but elementary truths about painting, yet unrecognised in Poland". Engaging in “fierce polemics” and fight “for their place under the sun”, they grafted Colourism onto the Polish art soil for decades to come. The approach gained ground in the Krakow milieu, where the former Formists Zbigniew Pronaszko and Tystus Czyżewski soon joined it; in time, it won support from some epigones of Modernism among the faculty of the Academy of Fine Arts. Two art groups thrived in Krakow that recognised colour as the prime means of expression: the “Jednoróg” (Unicorn) Association of Visual Artist (1925) and The “Zwornik” (Keystone) Union of Visual Artist (1928). Opposition against the hegemony of Colourism began to grow already in the mid 1930s. Young artists with leftist views, who idolized the Constructivist, Expressionist and Dada avant-garde, revolted against sensual painting. Picturalism, whose representatives began to gradually take over control of secondary and higher artistic education, and to exert more and more influence on the exhibiting policy, set the tone of Polish art until the outbreak of World War II. When the war was over, Colourists took the majority of key positions in culture institutions that were built from scratch in Poland. Their expansion was briefly interrupted by Socialist Realism, which, unlike Colourism, preferred what is painted to how it is painted. Colourists were also contested by the young avant-garde, who advocated abstraction, surrealism, and matière painting (or Matter Painting), and attacked Colourism from a political standpoints accusing them of supporting the socially hostile bourgeois circles and of formalised tastes. In the late 1950s the pre-war generation of Colourists was joined only by their trainees. Some, like Wacław Taranczewski (1903–1987) or Czesław Rzepiński (1905–1995), had had their artistic personalities shaped still in the 1930s. At that time Taranczewski was active in the group Pryzmat. His post-war works followed the principle of multiplying the motif, building images with the use of flat colour patches, sometimes enhanced with a line of distinct colour. Rzepiński had been associated with the Zwornik, and initially heavily influenced by Bonnard’s painting, later by Matisse and Braque. The next generation of Krakow Colourists is represented by Jan Szancenbach (1928–1999), who drew close to French Post-Impressionism by building images loaded with expressiveness achieved by strong colours, and Juliusz Joniak (b. 1925), who used a rich palette of vivid colours to paint shimmering landscapes and still lifes. Among the generation of artists born after the World War II, Colorism was brilliantly continued by Zbysław Maciejewski (1946–1999) and his sophisticated colour schemes in metaphoric images: at times dramatic, at times grotesque or lyrical. The Colourism showroom additionally features paintings by several Krakow-based artists who, while educated by celebrated figures like Emil Krch or Wacław Taranczewski, chose a different formula for their painting. Stanisław Rodziński (b. 1940) creates art imbued with mysticism, focused on the fundamental problems of human existence interpreted in the spirit of Catholic dogmas, and presented by means of simple, archetypal signs and low-key images, in which colour takes on symbolic functions. The oeuvre of Adam Wsiołkowski (b. 1949) is, on the contrary, associated with the geometric-and-romantic stream; his pieces build an active, alternative reality of ideal two- or three-dimensional shapes; this reality is governed by the laws of mathematics and physics, sometimes merging in autobiographic elements. Geometric abstraction was also the domain of Andrzej Ziębliński. Classicising tendencies in Polish art, which emerged still before World War I and flourished between the wars, are represented by sculptures of Wojciech Weiss (1875–1950) and Włodzimierz Konieczny (1886–1916), a painter, printmaker and poet, who died fighting in the Polish Legions. Modern post-war sculpture is further exemplified by a piece by Alina Ślesińska (1922–1994), who promoted a fusion of sculpture and architecture in her oeuvre. The showroom also surveys animated videos produced by filmmakers associated with the so-called Krakow school of animation. Among them are Kazimierz Urbański, Julian Antonisz, Jerzy Kucia, as well as Jan Lenica and Walerian Borowczyk. The mezzanine hosts theme exhibitions of Polish graphic arts, with a special emphasis on prints by Krakow artists. Urszula Kozakowska-Zaucha Wacława Milewska

dimensions: 200x137

author's label: Signed and dated upper right: Zb.1980; on the reverse the inscription: Zbysław Marek Maciejewski [...] SIMPATHIQUE, [...] 1980

exposition: The Gallery of 20th Century Polish Art,

The Main Building, 1, 3 Maja Av.

key: Colourism <<<

Polish artists’ interest in colour in the 1920s and 1930s was foretold by Józef Pankiewicz’s Post-Impressionist painting. His studio at Krakow’s Academy of Fine Arts soared in popularity among the students. The professor fired their imagination with conversations about early and contemporary art, Parisian museum and galleries, his friendship with Bonnard and curremt trends. In 1923 a group of Pankiewicz’s students set up what they called the Paris Committee – a community of those desiring to go to France to continue their education. They sought to create “good, pure” painting, i.e. painting free of any literary burden or historical and political responsibilities. The aim was to see reality through colour; to express light, space, shapes and other features of forms and events through colour. The motto: peinture – peinture! best summarised that approach. The chief ideologist of Kapism (from the Polish abbreviation “KP” for the Paris Committee) and the author of its artistic manifesto was Jan Cybis (1897–1972), a journalist, painter of dynamic, textured compositions that explore intensive, saturated colours and their mutual tensions. Another figure that dominated in the Krakow community of the Kapists was Zygmunt Waliszewski (1897–1936), a painter deeply rooted in French Post-Impressionism, and a suggestive illustrator of grotesque who used a classic, rich colour palette. Subtle Colourism marked the oeuvre of Hanna Rudzka-Cybisowa (1897–1988), who employed the pointillist technique to put down sensory interpretations of landscape, still life, and portrait. Like her husband Jan Cybis, she used distinct texture which not only accentuated the materiality of pigment, but also had a compositional function of integrating the image. Located between expression and impression, the creative output of Artur Nacht (later known as Nacht-Samborski, 1898–1974) from the very beginning stayed away from the radical Kapist programme. His clear, static compositions and sophisticated combinations of warm and cool colours had their dynamics enhanced by a discrete play of values. The painting of Józef Czapski (1896–1993) developed slightly diverging from the Kapist doctrine: both in the 1930s and, above all, in his post-war work, he opted for expression rather than the postulated colour to illustrate the ordinary, sometimes brutal day-to-day reality. Piotr Potworowski (1898–1962), initially also associated with the Paris Committee, gave up on Kapism and turned towards allusive abstraction using colour to boost dramatic tensions in his highly synthetic landscapes. A lot of Kapists returned to Poland in 1930–1931. As Czapski put it, they felt to be “advocates of absolute but elementary truths about painting, yet unrecognised in Poland". Engaging in “fierce polemics” and fight “for their place under the sun”, they grafted Colourism onto the Polish art soil for decades to come. The approach gained ground in the Krakow milieu, where the former Formists Zbigniew Pronaszko and Tystus Czyżewski soon joined it; in time, it won support from some epigones of Modernism among the faculty of the Academy of Fine Arts. Two art groups thrived in Krakow that recognised colour as the prime means of expression: the “Jednoróg” (Unicorn) Association of Visual Artist (1925) and The “Zwornik” (Keystone) Union of Visual Artist (1928). Opposition against the hegemony of Colourism began to grow already in the mid 1930s. Young artists with leftist views, who idolized the Constructivist, Expressionist and Dada avant-garde, revolted against sensual painting. Picturalism, whose representatives began to gradually take over control of secondary and higher artistic education, and to exert more and more influence on the exhibiting policy, set the tone of Polish art until the outbreak of World War II. When the war was over, Colourists took the majority of key positions in culture institutions that were built from scratch in Poland. Their expansion was briefly interrupted by Socialist Realism, which, unlike Colourism, preferred what is painted to how it is painted. Colourists were also contested by the young avant-garde, who advocated abstraction, surrealism, and matière painting (or Matter Painting), and attacked Colourism from a political standpoints accusing them of supporting the socially hostile bourgeois circles and of formalised tastes. In the late 1950s the pre-war generation of Colourists was joined only by their trainees. Some, like Wacław Taranczewski (1903–1987) or Czesław Rzepiński (1905–1995), had had their artistic personalities shaped still in the 1930s. At that time Taranczewski was active in the group Pryzmat. His post-war works followed the principle of multiplying the motif, building images with the use of flat colour patches, sometimes enhanced with a line of distinct colour. Rzepiński had been associated with the Zwornik, and initially heavily influenced by Bonnard’s painting, later by Matisse and Braque. The next generation of Krakow Colourists is represented by Jan Szancenbach (1928–1999), who drew close to French Post-Impressionism by building images loaded with expressiveness achieved by strong colours, and Juliusz Joniak (b. 1925), who used a rich palette of vivid colours to paint shimmering landscapes and still lifes. Among the generation of artists born after the World War II, Colorism was brilliantly continued by Zbysław Maciejewski (1946–1999) and his sophisticated colour schemes in metaphoric images: at times dramatic, at times grotesque or lyrical. The Colourism showroom additionally features paintings by several Krakow-based artists who, while educated by celebrated figures like Emil Krch or Wacław Taranczewski, chose a different formula for their painting. Stanisław Rodziński (b. 1940) creates art imbued with mysticism, focused on the fundamental problems of human existence interpreted in the spirit of Catholic dogmas, and presented by means of simple, archetypal signs and low-key images, in which colour takes on symbolic functions. The oeuvre of Adam Wsiołkowski (b. 1949) is, on the contrary, associated with the geometric-and-romantic stream; his pieces build an active, alternative reality of ideal two- or three-dimensional shapes; this reality is governed by the laws of mathematics and physics, sometimes merging in autobiographic elements. Geometric abstraction was also the domain of Andrzej Ziębliński. Classicising tendencies in Polish art, which emerged still before World War I and flourished between the wars, are represented by sculptures of Wojciech Weiss (1875–1950) and Włodzimierz Konieczny (1886–1916), a painter, printmaker and poet, who died fighting in the Polish Legions. Modern post-war sculpture is further exemplified by a piece by Alina Ślesińska (1922–1994), who promoted a fusion of sculpture and architecture in her oeuvre. The showroom also surveys animated videos produced by filmmakers associated with the so-called Krakow school of animation. Among them are Kazimierz Urbański, Julian Antonisz, Jerzy Kucia, as well as Jan Lenica and Walerian Borowczyk. The mezzanine hosts theme exhibitions of Polish graphic arts, with a special emphasis on prints by Krakow artists. Urszula Kozakowska-Zaucha Wacława Milewska